The arrival of Rockefeller Foundation officials in the Dutch East Indies presented the colonial government with a dilemma. On the one hand, they doubted the agency’s true mission, and on the other hand, it was difficult for them to refuse the Rockefeller Foundation’s arrival because of pressure from all sides and the fact that hygiene was not an easy task.

Hygiene Problems in the Dutch East Indies

Recently, Hans Pols (2018: 6), in his work entitled “Nurturing Indonesia: Medicine and Decolonization in the Dutch East Indies,” stated that until the 19th century, the Dutch East Indies was considered one of the most unhealthy places in the world.

According to colonial-era research, the statement is not just an opinion, given that there were several outbreaks due to poor sanitation at the time. Also, because of the frequent mass deaths at the time, Batavia is known as a cemetery for Europeans (Pols, 2012: 126).

In some cases, the Dutch see locals as the source of the disease that infects them. However, after further investigation, epidemic diseases such as cholera and hookworm were caused by various factors such as poor housing conditions and lack of sanitation facilities.

The cholera epidemic of the 19th and early 20th centuries was an example of a disease caused by poor sanitation. According to A.E. Waszklewicz (1867:77-78), head of the health service, cholera outbreaks were caused by a poor disease diagnosis and exacerbated by poor sanitary conditions.

A similar case of poor sanitation occurred in the Gombong area in the mid-19th century. In the region, trachoma ravages military training camps, blinding students. Trachoma was initially suspected among the local civilian population but has been traced to oversized building occupants, lack of lighting, and poor sanitation (Persknaire, 1898: 550).

In the early 20th century, epidemics caused by poor sanitation continued. C. L. van Steeden (1901: 211-236) described the results of his research on the hookworm endemic to Sawah Lunto in West Sumatra in an article entitled “Anchylostomiasis, de oorzaak van de endemic progressieve pernicieuse anaemie onder de mijnwerkers te Sawah-Loento”.

The larvae of Ankylostoma cause the disease, leaving patients with severe anemia. He concluded that the unsanitary environment allowed the beetle larvae to reproduce and spread through eating and drinking. To this end, he suggested that miners wash their hands before meals, drink clean water, and defecate in designated places.

The Role of the Rockefeller Foundation in the Dutch East Indies

As the name suggests, the Rockefeller Foundation is inseparable from the role of the Rockefeller family. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, John D. Rockefeller Sr. became the central figure of the family.

Much of the Rockefeller family’s wealth came from the Standard Oil Company, founded in 1870. In a short time, the company became the oil company that dominates the world oil trade.

John D. Rockefeller Sr.’s interest in the world of health began to grow in the 20th century. In 1901, he founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. But establishing the agency is only the first step toward a larger health and humanitarian mission.

In 1909, John D. Rockefeller Sr. donated 72,000 Standard Oil shares worth $700 million to fund what would become known as the Rockefeller Foundation. The planned agency aims to reach a wider area not only in the United States.

After much planning, the Rockefeller Foundation was established on May 14, 1913, officially named the “International Sanitary Commission,” with Wycliffe Ross as its first director. The hookworm problem and public health have been the agency’s top priorities since its inception (Farley, 2003:3-4).

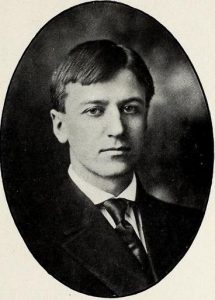

Two years later, the Rockefeller Foundation sent its representative Dr. Victor Heiser to Java. Heiser’s mission is to spread the U.S.-approved hookworm control method to different parts of the country.

When he arrived in Java in March 1915, his strategy for approaching the government was very simple. First, he looked around some of Batavia’s slums to learn about hygiene, then met with medical staff at a government laboratory. Learn about the methods of colonial government.

His arrival was so warmly received that he could meet the Governor at his office in Bogor on the third day. The Governor has expressed a keen interest in the approach of the International Health Commission (IHC) to tropical health issues. He wishes to raise the issue with his Chief Medical Officer. The Governor’s response sparked optimism in Heather, who continued to travel from Batavia to Singapore.

After more than a year, Heiser returned to Java. This time he started the journey from Surabaya to Batavia. Heiser’s second visit also agreed that the following year, Dr. Samuel T. Darling was able to start his research on hookworms in the Dutch East Indies.

Data from 12 sample areas examined by Darling’s team found that “at least 90% of the Java population is infected with hookworm disease. Most infections occur in the densely populated Central Java population through unhealthy habits, and irrigation systems, which allow infection from a single area Rapidly spread to another area. In addition, another fact is that the severity of the patient will be more severe if he also suffers from malaria; further attention should be paid to malaria-prone areas (Hull, 2007: 142).

More than a year later, Heiser returned to Java. This time he started his journey from Surabaya to Batavia. Heiser’s second visit also agreed that the following year, Dr. Samuel T. Darling was able to start his research on added worms in the Dutch East Indies.

Data from 12 sample areas examined by Darling’s team found that “at least 90% of the Java population is infected with hookworm disease. Most infections occur in the densely populated Central Java population through unhealthy habits and irrigation systems, which allow infection from a single area Rapidly spread to another area. In addition, another fact is noted that the severity of the patient will be more severe if he also suffers from malaria; further attention should be paid to malaria-prone areas (Hull, 2007: 142).

With the first report of the Darling Commission, the collaboration between the Rockefeller Foundation and the colonial government began. However, when cooperation was in sight, the colonial government unilaterally refused.

The reason is that, in the Darling Commission report, the Chief Health Officer cited a photo of a worker that said, “Men and women became transport animals in the great struggle for survival on the beautiful island of Java.” On the other hand, the negativity of health service directors looking to use their own people to eradicate hookworm is bolstered.

The issue has delayed the partnership plan by up to eight years. During this time, Heather continued pressuring the colonial government to accept the Rockefeller Foundation’s mission.

Competition between the International Health Commission and the Colonial Health Service

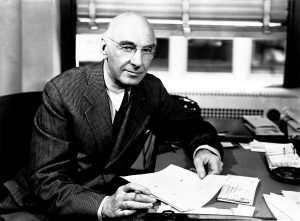

Heather’s efforts paid off, and on April 10, 1924, two officers of the Rockefeller Foundation, Dr. John Lee Heydrick, and Dr. Van Nott. Came to Java for a hookworm control demonstration project.

Unfortunately, neither partner was the right partner. Hydrick is a Dutch-American who served in the United States and the Caribbean Islands. Meanwhile, Van Nott was a Dutchman who served in Java. He was recruited to simplify projects in the Dutch East Indies.

But during the trip, Van Nott didn’t want to cooperate or follow the Foundation’s instructions. Hydrick also reported his partner’s behavior to Heiser, which led to van Noort’s exit from the Dutch East Indies.

In carrying out its mission, the Rockefeller Foundation and the colonial government had very different attitudes.

IHC officials prioritized educational approaches. By working with Javanese, Hydrick started the program. Hydrick (1942:75) also asserted, “It is more important for the community to learn to use the latrine, thereby preventing general contamination of soil and water. Furthermore, the community must first learn how to use the latrine and keep it clean. , you can raise the question of improving toilet types and materials.”

Meanwhile, the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies leaned more toward dictatorship. In this way, the colonial government emphasized supplying pharmacies with quinoa (an anthelmintic drug) and asked local district leaders to give residents subtle instructions on building toilets. From the point of view of the health sector, the authoritarian approach is necessary because they generally consider Javanese to be “lazy.”

Different practices also lead to differences in application areas. Hydrick started its program in the Bantam district of Banten, and the health department carried out the program in the Kroja district of Central Java (Hull, 2007: 143).

From the outset, Dutch officials had no idea that Rockefeller’s educational and advocacy methods would be successful in the Dutch East Indies. They even argue that these projects may disrupt indigenous customs and traditions in Javanese villages (Gouda, 2009).

According to research by Susan Engel and Anggun Susilo, the rivalry between the two parties is more likely that colonial government officials want Rockefeller Foundation funding without involving officials and their methods.

In his research, Hull tried to compare the results of the two sides. By 1926, the health service had successfully built 150,000 toilets, but few were using them. Meanwhile, the Rockefeller Plan didn’t build many toilets, but they were all used, and residents were enthusiastic about the sanitation program being implemented.

The enthusiasm generated is inseparable from the educational methods used. Before the sanitation spell came to a village, the IHC team hosted a screening of a film called “Unhooking Hookworms,” which used to be called komidhi sorot as an educational tool. Movies spread clean propaganda, and the public can easily grasp the information. After watching a movie, people usually prefer to have a mandala visit at home (Stein, 2006: 19).

It’s hard to deny that the approach introduced by the Rockefeller Foundation offered something new in the Dutch East Indies. Despite initial objections, colonial officials could not turn a blind eye to the continued use of this method.

Although Hydrick left the Dutch East Indies in 1939, many Javanese doctors were inspired by Hydrick’s plans, including Abdul Rasjid. In 1935, while visiting the experimental area of the Rockefeller Project in Purwokerto, he expressed his admiration that “all the ideas of public health that I have always cherished were fully applied” (Pols, 2018: 152).

Even after the Revolutionary War, Indonesian doctors tried establishing a Hydrick school to train nurses in hygiene. They claim this was for the Indonesian state’s future rural cleanup project (Stein, 2006:20).

Bibliography

Farley, John. To Cast Out Disease: A History of The International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation (1913-1951). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Gouda, F. “Discipline versus Gentle Persuasion in Colonial Public Health: The Rockefeller Foundation’s Intensive Rural Hygiene Work in the Netherlands East Indies 1925-1940” Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports Online, 2009.

Hull, Terence H.. “Conflict and collaboration in public health The Rockefeller Foundation and the Dutch colonial government in Indonesia” dalam Milton J. Lewis (Ed.). Public Health in Asia and the Pacific. Oxon: Routledge, 2007.

Hydrick, J. L. (1942). Intensive Rural Hygiene Work in the Netherlands East Indies. New York:

Booklets of the Netherlands Information Bureau, No. 7.

Pols, Hans. “Notes from Batavia, the Europeans’ Graveyard: The Nineteenth Century Debate on Acclimatization in the Dutch East Indies”. Journal Of The History Of Medicine And Allied Sciences, Volume 67, Number 1, 2011.

_______. Nurturing Indonesia Medicine and Decolonisation in the Dutch East Indies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Steeden, C. L. van. “Anchylostomiasis, de oorzaak van de endemische progressieve pernicieuse anaemie onder de mijnwerkers te Sawah-Loento.” Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 1901, hlm. 211-236.

Stein, Eric A. “Colonial Theatres of Proof: Representation and Laughter in 1930s Rockefeller Foundation Hygiene Cinema in Java”. Health and History, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2006.

Waszklewicz, A. E. “Cholera-Epidemie In 1864”. Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 1867, hlm. 78-80.