Undertaking the Hajj pilgrimage during the colonial era proved to be a formidable challenge. In addition to the less advanced transportation infrastructure compared to modern times, pilgrims were frequently subjected to deception by Hajj organizers. High and manipulative tariffs often resulted in pilgrims accumulating substantial debts.

Table of Contents

The Zeal of the Dutch East Indies Population for the Hajj Pilgrimage

The precise origins of the Hajj pilgrimage among Indonesian Muslims remain challenging to establish. Historical records suggest that as early as the 16th century, Nusantara pilgrims were already making their way to Mecca.

According to the account of Louis Barthema, the pilgrims he encountered in 1503 were Nusantara traders who had docked in Jeddah and availed themselves of the opportunity to visit Mecca.

By the 17th century, Nusantara Muslims journeyed to Jeddah not solely for trade purposes, but also to pursue studies in Mecca and Medina. During their educational sojourns, many of them chose to reside in the holy land for extended periods. Upon their return to their homeland, some of these individuals assumed roles as religious teachers or preachers, disseminating the knowledge they had acquired in Mecca and Medina.

Beyond its religious and educational dimensions, it’s worth noting that some pilgrims of noble lineage embarked on their journey to Mecca in pursuit of political legitimacy and the consolidation of power. This is exemplified by events in 1630 when the Kings of Banten and Mataram engaged in a rivalry for the acknowledgment of their authority. They made the arduous voyage to Mecca with the objective of securing the honorific title of “Sultan” from Mecca’s authorities, as they believed it would confer spiritual potency upon their reigns.

Throughout the years, the allure of the Hajj pilgrimage has continued to captivate Indonesian Muslims, and this fervor persists to the present day. Nevertheless, Indonesian Hajj pilgrims continue to grapple with many of the historical challenges, including transportation issues, Hajj passports, Hajj fees, the quality of Hajj services, security, and accommodations.

In the 18th century, the Hajj pilgrimage evolved into a cherished aspiration for countless indigenous Muslims. Undertaking the Hajj was not solely a means of fulfilling the fundamental tenets of Islam, but it also became a source of profound social pride. Initially, this pilgrimage was no easy feat due to the scarcity of amenities and the protracted duration of the voyage, primarily relying on sailboats, rendering it beyond the means of many.

Nonetheless, the fervor among Muslims to embark on this sacred journey, the fifth pillar of Islam, the Hajj, exhibited persistent growth. For shipping companies, this phenomenon undoubtedly presented a promising opportunity.

Facilitated by intermediaries, these shipping companies actively encouraged the indigenous population to partake in the Hajj by availing themselves of their vessels. At times, these intermediaries even prevailed upon those of modest means, despite their financial constraints, to undertake the Hajj. This sometimes extended to individuals whose economic circumstances did not enable them to meet the Hajj’s financial prerequisites, both for themselves and their families left behind.

Conversely, Arab governments have long recognized the considerable economic potential associated with the pilgrimage. The authorities in the Hijaz region, in particular, placed significant emphasis on attracting pilgrims from the Dutch East Indies owing to their substantial numbers. Consequently, they made concerted efforts to cultivate and enhance cordial relations with the Dutch East Indies Colonial Government.

To this end, the Hijaz region proactively dispatched propagandists to the Dutch East Indies to maximize the number of pilgrims. Over time, this engendered a collaborative rapport among the colonial government, shipping companies, and the Arab government.

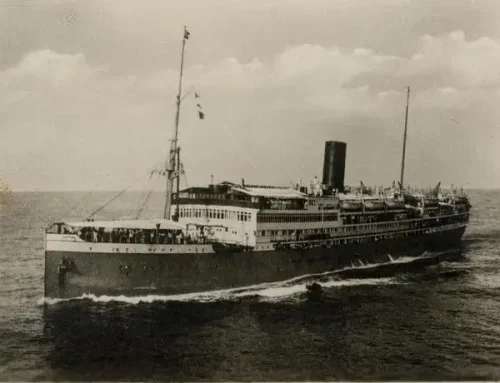

In the context of the Hajj pilgrimage, the availability of ships holds paramount importance, as they serve as the primary mode of transportation to reach the holy land. The modernization of Hajj transportation, transitioning from sailing ships to steamships, precipitated a significant upsurge in the number of Indonesian pilgrims.

During the early 20th century, the count of Dutch East Indies pilgrims witnessed rapid growth. In 1911, Indonesian pilgrims constituted 28.7 percent of the total pilgrims in Jeddah. Subsequently, in 1927, this proportion surged to nearly half of the world’s pilgrims, reaching 43.7 percent. The pilgrimage encountered a substantial decline only when it was temporarily suspended, notably during World War I and the Malaise Crisis.

Transport to the Holy Land

In the pre-modern era, embarking on the Hajj pilgrimage posed formidable challenges. Pilgrims’ journeys to Arabia were contingent upon seasonal conditions and the availability of ships.

The sailing ships predominantly employed for this purpose did not typically offer direct routes to Jeddah. As a result, pilgrims had to undergo multiple ship transfers to reach their ultimate destinations, such as Jeddah or Yemen. For instance, the voyage from Batavia (present-day Jakarta) necessitated stops in Aceh, followed by further travel to India, before eventually arriving in Hadramaut or Jeddah.

This demanding pilgrimage necessitated that pilgrims be well-prepared for an array of perils throughout the journey, including the risk of food shortages, loss of personal belongings, and, regrettably, even the risk of losing their lives. Pilgrims had to ensure they were in optimal physical condition, possess unwavering courage, have substantial financial resources, stock up on provisions, and make suitable financial provisions for the families they left behind.

However, these challenges did not diminish the enthusiasm of Nusantara Muslims for undertaking the Hajj. Paradoxically, these difficulties endowed the pilgrimage with profound meaning and rich experiences for them.

The advent of steamships, coupled with the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869, sparked a surge in the interest of Dutch East Indies pilgrims. More ships, originating from Java and Singapore, began to traverse the Suez route.

During the 19th century, the Dutch, who had regained control of the archipelago, initially refrained from becoming involved in the administration of the pilgrimage. Instead, the British became the first nation to recognize the potential of the increasing number of pilgrims in the archipelago and initiated the provision of Hajj transportation services employing steamships.

In 1858, the British commenced the operation of steamships for conveying pilgrims from Batavia (present-day Jakarta) to Jeddah. This endeavor proved immensely lucrative for British shipping companies, given the limited availability of Hajj transport alternatives during that period.

Recognizing the burgeoning opportunities, the Arab community in Batavia entered the fray by acquiring a vessel from Besier en Jonkheim. This ship boasted the capability to convey 400 pilgrims from Batavia to Padang and onward to Jeddah.

The optimistic prospects also compelled the Dutch to become actively involved. In 1872, they established a Dutch Consulate in Jeddah, marking the direct participation of the Netherlands in the administration of the Hajj journey.

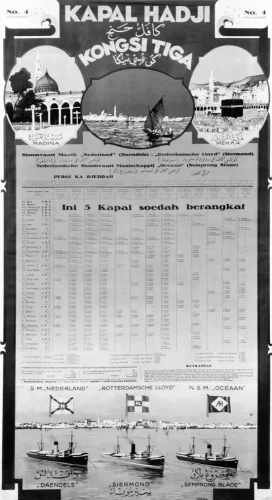

A year later, in 1873, the Dutch brokered a contract for pilgrim transportation with three shipping companies: Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland, Rotterdamsche Lloyd, and Nederlandsche Stoomvaart Maatschappij Oceaan, collectively known as the “Kongsi Tiga.” The Kongsi Tiga held a monopoly over the conveyance of pilgrims from the Dutch East Indies until the conclusion of the colonial era.

The Hajj Journey

When an individual resolved to embark on the Hajj journey, they had the flexibility to select the port and the vessel of their preference. During the early 20th century, there were a minimum of three options for commencing the journey to Jeddah.

Firstly, they could opt for one of the Kongsi Tiga ships available at ports in the Dutch East Indies. Secondly, they could choose to board a vessel originating from the Malay Peninsula, departing from embarkation points in Singapore and Penang. Thirdly, they had the option to utilize public maritime transport and then commence their journey to Jeddah from Bombay or Suez.

To ensure efficiency and a well-organized system in Mecca, Dutch authorities categorized the pilgrims into three distinct arrival groups:

1. The Padang group, encompassing pilgrims departing from Sabang, Bengkulu, and Teluk Betung.

2. The Palembang group, including pilgrims departing from Belawan, Palembang, Jambi, Muntok, and Sabang.

3. The Batavia group, accommodating pilgrims departing from Tanjung Priuk and various other Javanese ports.

The conditions for Hajj pilgrims departing from Singapore differed from those in the Dutch East Indies. Hajj pilgrims embarking on British ships typically did not require passports and visas. British ships could transport Hajj pilgrims with just a single ticket, which at times was more economical compared to Dutch ship tickets. Additionally, British ships often did not mandate vaccinations for diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and smallpox.

Conversely, Dutch ships were generally more expensive, and Hajj pilgrims were obliged to purchase round-trip tickets. Hajj pilgrims from the Dutch East Indies also had to fulfill specific vaccination requirements before departure.

These differing conditions could have been one of the factors influencing the choices made by Hajj pilgrims when selecting ships and embarkation points that aligned with their needs and preferences. Hajj pilgrims from British colonies like Singapore, Bombay, and Penang enjoyed certain advantages in terms of travel requirements and ticket costs, making their journeys more convenient and affordable.

The choice of British ships as a means to undertake the pilgrimage carried its own set of risks for the Dutch East Indies pilgrims. Traveling on a British ship meant that they were entrusting their safety to a vessel outside the jurisdiction of Dutch authorities, making it challenging for them to report any issues or problems that arose during the journey.

Certain British shipping companies, such as Herklots and Alsegoff & Co, have been found to engage in harmful and exploitative practices against Dutch East Indies pilgrims. These companies deceived pilgrims by overcharging them for transportation, resulting in a burden of debt for the pilgrims.

In some instances, pilgrims who could not repay their debts ended up as indentured laborers on the plantations owned by the shipping companies. They were compelled to work under harsh conditions and receive low wages for several years as a means to settle their debts.

The Dutch consul in Jeddah made efforts to raise awareness and take action against shipping companies like Herklots. However, the local regulations in Jeddah tended to favor and protect these companies, limiting the extent to which the Dutch consul could effectively shield pilgrims from exploitation.

The Sheikh’s Role in Attracting Hajj Pilgrims

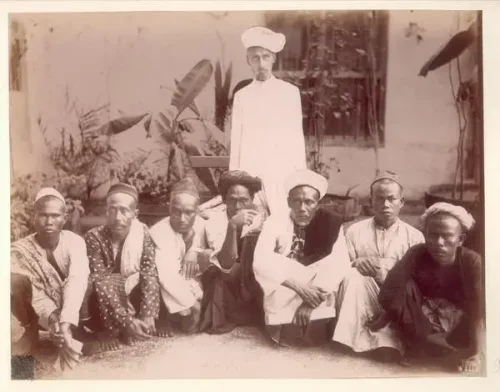

The significant enthusiasm of the Dutch East Indies population to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage is closely intertwined with the intermediary role played by sheikhs between the pilgrims and the shipping companies. Pilgrims typically did not purchase tickets directly from shipping agents but rather through these sheikhs.

In fulfilling their intermediary role, the sheikhs heavily depended on the number of customers and the profits they could generate. The greater the number of pilgrims they brought, the larger the commission they received from the shipping companies. Consequently, sheikhs competed among themselves and often sold tickets at high prices.

Observing this phenomenon, potential pilgrims frequently opted for journeys from Singapore, where ticket prices and sheikh fees were more affordable. Nonetheless, the lower ticket prices sometimes led to ships overcrowding with passengers, with limited focus on ensuring the safety and comfort of the travelers.

Furthermore, the sheikhs frequently engage in deceptive practices, presenting a false image of the actual conditions on board. This is a result of the pressure they face from the shipping companies to maximize the number of passengers.

These adverse circumstances are compounded by the ships’ poor hygiene and sanitation, along with limited food provisions. Pilgrims often find themselves consuming unsuitable food, including inadequately cooked or undercooked rice. These collective challenges contribute to a grueling and distressing Hajj travel experience for the pilgrims.

Deception of pilgrims is not limited to the voyage; it extends to their arrival in Jeddah. Many of the sheikhs’ promises regarding transportation from Jeddah to Mecca go unfulfilled.

In a particularly dire case, approximately 100,000 pilgrims were compelled to make the arduous journey on foot from Jeddah to Mecca due to the unavailability of transportation. Consequently, the pilgrims endured immense suffering during the journey, with many falling ill and experiencing severe dehydration.

Snouck Hurgronje recognized the gravity of this issue. He realized that the primary source of the problem was not the sheikhs but rather the shipping companies, which operated with arbitrary and profit-driven practices. Therefore, he proposed that the central government should step in to address these fraudulent activities.

Despite the controversies surrounding their role, intermediaries remain indispensable for shipping companies, particularly the Kongsi Tiga. Their involvement is essential for attracting customers, especially in rural areas where the companies would struggle to establish a presence without them.

Resistance to the ” Kongsi Tiga” Monopoly

During the 1930s, as the Muslim intellectual community in the Dutch East Indies expanded, a chorus of voices condemning the abuses of the shipping companies gained momentum.

These critiques were prominently featured in various local newspapers. Kongsi Tiga, in particular, was the target of severe allegations. They were accused of treating pilgrims like mere commodities, cramming them onto the ships in inhumane conditions. The treatment of pilgrims was likened to that of contract coolies, disregarding their status as religious travelers. Furthermore, a violation of Islamic principles was noted as there was no provision for the segregation of men and women on the ships.

After enduring years of frustration and discontent, Muslims from the Dutch East Indies began to recognize the necessity of having authority over the Hajj. This realization led to the establishment of their own Hajj bureau and shipping company. The motivation behind this initiative was the conviction that the organization of the Hajj should be under Muslim control, rather than being monopolized by Europeans for profit.

The reformist Islamic organization Muhammadiyah played a significant role in promoting this idea by attempting to charter ships for transporting pilgrims. They successfully founded a shipping company called Penoeloeng Hadji (PH). To accomplish this, Muhammadiyah embarked on a campaign to raise 500,000 Dutch guilders for chartering a ship. This endeavor marked their initial efforts to challenge the hajj shipping monopoly and grant Muslims greater influence over their pilgrimage.

The Penoeloeng Hadji (PH) shipping company adopted a distinct approach compared to Dutch firms like Kongsi Tiga. Their primary focus was on the welfare and needs of the pilgrims, and they were dedicated to enhancing the services and amenities available to prospective pilgrims. Despite offering similar rates to Kongsi Tiga, PH was determined to offer a superior level of comfort and convenience to the pilgrims.

PH introduced a range of amenities, including separate prayer areas for men and women, training programs for prospective pilgrims during the journey, dining facilities, libraries, radio access, and a medical team comprising doctors and nurses. These facilities were designed with the intent of ensuring the well-being and comfort of the pilgrims, with the goal of preventing them from falling into debt due to the expenses associated with the Hajj pilgrimage.

While Kongsi Tiga initially downplayed PH’s efforts and questioned the capability of the native population to manage Hajj transport, Kongsi Tiga had its own concerns. The survival of their monopoly heavily relied on legal support and the colonial government’s backing.

Kongsi Tiga’s interests were deeply entwined with the 1922 Hajj Ordinance, which provided a legal framework for their operations. According to this ordinance, transport companies were obligated to obtain a license and provide a guarantee of ƒ90,000, a considerable sum that was not easily attainable for a newly established company.

In their quest to secure the license, Muhammadiyah employed their grassroots network to raise the necessary ƒ90,000. This fundraising effort included personal donations from affluent members of the organization, as well as contributions solicited from each prospective pilgrim. These contributions were intended to be later deducted from the pilgrims’ Hajj fares, and Muhammadiyah maintained that their approach adhered to the existing regulations without violating them.

Kongsi Tiga expressed serious concerns that Muhammadiyah’s actions were illegal and constituted violations of existing regulations. In order to safeguard its interests and prevent potential interference from Muhammadiyah, Kongsi Tiga took the step of submitting an official report to the colonial government. This report detailed the financial transactions conducted by PH representatives with prospective pilgrims.

Through this report, Kongsi Tiga sought to assert its dominance and demonstrate its authority to Muhammadiyah and other native organizations interested in establishing a Hajj organizing bureau. Their aim was to underscore that their monopolistic interests were not only upheld by colonial laws but also enjoyed the support of the colonial government.

Nevertheless, Kongsi Tiga remained apprehensive that Muhammadiyah might attempt to circumvent the ƒ90,000 guarantee requirement by exploiting Article 67 of the Hajj Ordinance. They were concerned that Muhammadiyah might present PH as a non-profit organization motivated solely by ethical considerations for dispatching pilgrims.

In an effort to address the escalating situation, representatives of Kongsi Tiga held a meeting with the Hoofdinspecteur van Scheepvaart (Superintendent of Shipping) to discuss the recent interactions between the Hoofdinspecteur, three leaders of Muhammadiyah, and the Adviseur voor Inlandsche Zaken (Advisor for Indigenous Affairs).

Following this meeting, the Hoofdinspecteur and the Adviseur issued a strict prohibition, forbidding Muhammadiyah from engaging in the organization of the Hajj. They argued that such involvement would be detrimental to both parties. Muhammadiyah vehemently expressed its dissatisfaction with this decision, viewing it as a confirmation of Kongsi Tiga’s continued monopoly.

As a result of the Hoofdinspecteur’s decision, the Penoeloeng Hadji Muhammadiyah ship was prevented from setting sail during 1931-32. Nevertheless, the desire to have their own means of transport for the Hajj pilgrimage remained steadfast, and Muhammadiyah continued to critique the monopoly maintained by Kongsi Tiga until the end of the colonial period.

Bibliography

Alexanderson, K. (2014). “A dark State of affairs”: Hajj networks, Pan-Islamism, and Dutch colonial surveillance during the interwar period. Journal of Social History, 47(4), 1021-1041.

Ichwan, M. N. (2008). Governing Hajj: politics of Islamic pilgrimage services in Indonesia prior to reformasi era. Al-Jami’ah: Journal of Islamic Studies, 46(1), 125-151.

Miller, M. B. (2006). Pilgrims’ progress: the business of the Hajj. Past & present, 191(1), 189-228.

Rohmana, J. A. (2015). A Sundanese Story of Hajj in the Colonial Period: Haji Hasan Mustapa’s Dangding on the Pilgrimage to Mecca. Heritage of Nusantara: International Journal of Religious Literature and Heritage, 4(2), 273-312.

Ryad, U. (2016). The hajj and Europe in the age of empire (p. 286). Brill.

Supratman, F. R. (2020). Hajj and the chaos of the Great War: Pilgrims of the Dutch East Indies in World War I (1914-1918). Wawasan: Jurnal Ilmiah Agama dan Sosial Budaya, 5(2), 167-178.Tantri, E. (2013). Hajj Transportation of Netherlands East Indies, 1910-1940. Heritage of Nusantara: International Journal of Religious Literature and Heritage, 2(1), 119-147.