When we talk about people with disabilities, it’s hard to rule out the discrimination that has plagued their lives. As human beings, it is difficult for them to acquire human rights, one of which is the right to learn. It can be said that education is strange to them. With no education since childhood, their psychological and intellectual development is hindered, and their future slowly turns dark. The discourse on educating the disabled emerged in the Age of Enlightenment, marked by the emergence of humanist philosophers and the establishment of schools for people with disabilities.

The life of the disabled in the Middle Ages

For centuries, persons with disabilities have faced difficult and tragic situations due to various forms of discrimination.

In the society of this period, the concept of diffable is very different from today. In fact, people with disabilities of all types and levels are not considered human, but are classified as “idiots,” a term that comes from Greece.

Through this term, disabled people are not considered part of citizenship, which means they have no rights in the public sphere, they are not part of public policy, and they do not have the right to marry and have children.

To use the word idiot, disabled people are excluded from the social system and considered strange, incompetent, and undeserving of their rights as human beings. Eventually, they turned into a hopeless minority begging in the streets.

There are no significant reforms to improve the lot of people with disabilities, who are considered incapable of understanding any form of guidance and education in dark age societies. So no attempt was made to educate them.

This is exacerbated by the emergence of the belief that disability is caused by either God’s punishment or the devil’s curse. Therefore, society at the time believed that the fate of the disabled could be improved only through God’s intervention. The emergence of this belief can be traced back to the countless magical healing stories of this era.

Schools for people with disabilities

In the mid-18th century, the winds of change for disabled people began to blow, starting in Europe. The intellectual engineering of the Age of Enlightenment aimed at building knowledge, humanistic philosophy, and democratic thought led to the concept of equal rights for all mankind.

In this idea of equality, all people have the responsibility to care for others, especially individuals outside the family.

The discourse of improving the fate of the disabled cannot be separated from the rise of the reform movement in this century. These movements have a humanitarian mission, especially fighting for the rights of fellow citizens and reducing the suffering of others, including people with disabilities.

In France, represented by Enlightenment philosophers such as Diderot, Voltaire, and Candillac, the spirit of reform has been most clearly reflected. They abandoned the speculative metaphysics of the last century in an attempt to change the perspective of human beings too concerned with religious issues, towards social awareness and sensitivity to fellow human beings. Their philosophy proposes to improve the welfare of individual groups, including the poor, slaves, and disabled people who have always been excluded.

France has become a fertile ground for the development of ideas to improve the fate of persons with disabilities. In the region, the idea of educating people with disabilities and building schools is growing. Education for the disabled is first for the deaf, then for the blind, and finally for the mentally handicapped. The concept of disability education spread from France to the rest of Europe.

The development of the field of disability education in France is deeply influenced by John Locke’s theory, which holds that human beings are born without innate spiritual content, as empty as paper, and that all human knowledge is acquired little by little through experience and perception. perception of the external environment.

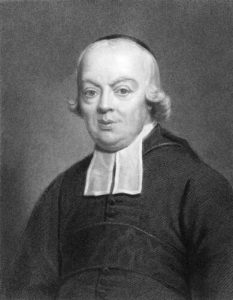

John Locke’s theory was later adopted by Abbé Charles Michel de l’Epée (1712-1789), a French priest, who assimilated it with the ideals of equality and combined it with a new concept of sign language for the deaf. Thanks to his efforts, he succeeded in devising an innovative method of education for the deaf, which was later implemented between 1750 and 1760 by establishing the world’s first disabled school (now the National School of Youth in Paris). The school opened to the public in 1760.

Epée’s idea of promoting sign language was revolutionary at the time. His success in sign language education seems to be telling the world that people with disabilities can actually be educated and developed, as long as they use the right educational methods according to their needs.

Many people are fascinated by this intellectual revolution. Epée’s influence ultimately does not only affect education for the deaf, but also inspires other disabled groups such as the blind and mentally retarded to obtain education.

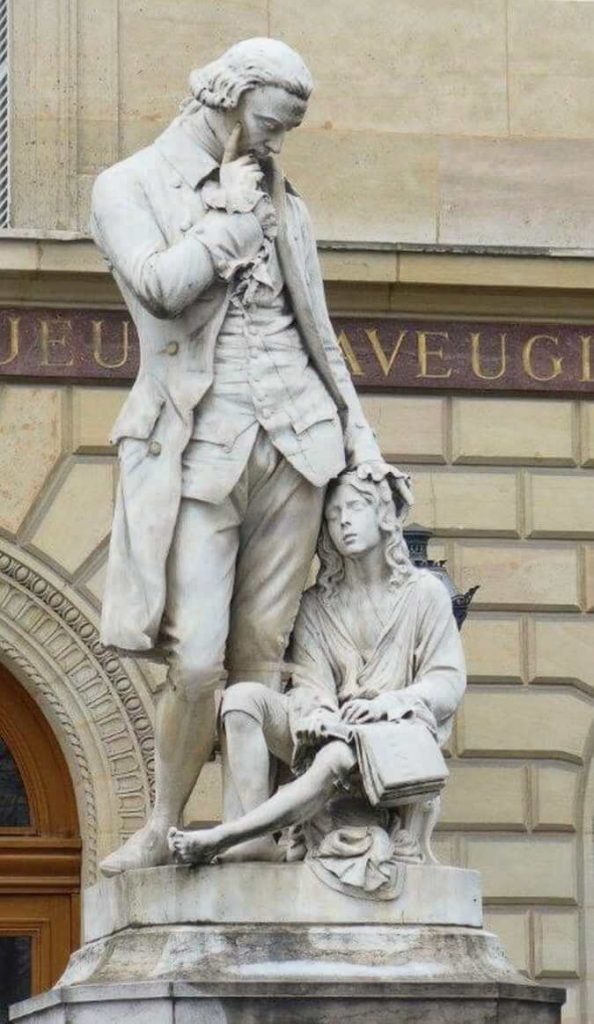

After Epée, Valentin Hauy became an influential figure in disability education. The story begins in May 1784 when he meets Francois Leseur, a blind beggar, in the streets of Paris. Hauy noticed that Lesser could tactilely read the nominal amount he gave him.

Reforms in the treatment of people with mental disabilities also emerged in the Enlightenment, expressed by Philippe Pinel (1745-1826), also known as the first psychiatrist in France. Pinel introduces a more humane and methodological ethical approach to diffables. Through his efforts, Pinel began transforming institutions that housed the disabled into mental hospitals.

After the Pinel reform, the idea of educating people with mental disabilities also emerged. Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard became the man who started the company in 1800 by teaching an autistic child named Victor.

Despite all the difficulties, especially in the teaching of spoken language, Victor has experienced significant development, especially in his attitude towards others.

Itard’s efforts were then continued by his pupil Edouard Seguin. Driven by the zeitgeist of the Enlightenment, Senguin believed that education was a universal right and that society had an obligation to improve the fate of others, including those with intellectual disabilities. For Senguin, the task of educating them is part of a wider social movement aimed at abolishing social classes and creating a just society.

In 1839, Senguin successfully established a private school for people with intelectual disabilities. At that school, he developed educational methods to take care of them. According to his revolutionary discovery, people with intellectual disabilities are not people with limited intelligence due to disease or brain abnormalities, but rather have stunted mental development. So, the solution to training them is to do sensory training. His integrative approach was later used as the basis for nearly all institutions and education for children with mental disabilities in the 19th century.

The first three disabled schools carried out a normalization mission for the disabled. Under this mission, they hope to educate people with disabilities to become independent people, free from the dependencies that have so far plagued them. With sufficient knowledge and skills, persons with disabilities are expected to be able to return to their place of origin and be able to integrate with the public.

The impact of the French education reform for the disabled then spread all over the world. Following the pioneers in France, reform movements to fight for the right to education for the deaf, blind, and mentally handicapped are also emerging in Europe and the United States. Over time, disabled schools have spread to all corners of the world. In fact, methods discovered in the Age of Enlightenment are more or less employed today.

Bibliography

Flugel, J. C., & West, D. J. A hundred years of psychology (3rd ed.). London: Duckworth, 1964.

Kauffman, J. M. “Nineteenth century views of children’s behavior disorders: Historic contributions and continuing issues”. Journal of Special Education, 10, 1976, p. 335–349.

L’Epée, Charles-Michel. The Method of Educating the Deaf and Dumb: Confirmed by Long Experience. London: George Cooke, 1801.

MacMillan, M. B. “Extra-scientific influences in the history of childhood psychopathology”. American Journal of Psychiatry, 116, 1960, p. 1091–1096.

Perkins Institution for the Blind. Annual reports of the trustees of the New England Institution for the Education of the Blind to the corporation. Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1881.

Wilson, Arthur M. Diderot. New York: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Winzer, Margret. A. “A tale often told: The early progression of special education”. Remedial and Special Education, 19, 1998, p. 212–218.

Winzer, Margret A. From Integration to Inclusion: A History of Special Education in the 20th Century. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press, 2009.

Winzer, Margret. A. The history of special education: From isolation to integration. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1993.

Excellent post! We are linking to this great content on our website.

Keep up the good writing.