Through the Fabriek Bond personnel, Soerjopranoto mobilized a mass of workers to protest against the injustice of business owners and the colonial government. In the aftermath of his actions, the colonial government nicknamed him Stakings Koning, aka the strike king.

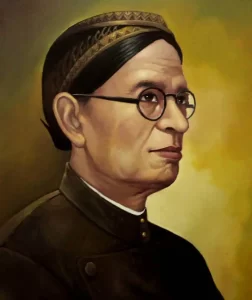

The Down-to-Earth Nobleman: Raden Mas Soerjopranoto

Not many aristocrats are willing to live among ordinary people. Living in luxury is the most common stereotype for this class.

However, not all aristocrats are indifferent to the plight of the commoners. Soerjopranoto was one of them. Born in Pakualaman on January 11, 1871, Raden Mas Soerjopranoto spent much of his life fighting for the fate of oppressed workers.

Soerjopranoto’s father, Prince Aryo Suryaningrat, was the eldest son of Pakualam III. Unfortunately, his blindness eliminated him from the position of heir to the throne.

Pakualam III’s successor was Suryaningrat’s cousin, Suryo Sasranigrat (Pakualam IV). He was known to live a glamorous life and liked to party. Habits that eventually dragged the Pakualaman family into a financial crisis.

This situation forced Suryaningrat and his children to leave the palace and live modestly. Living outside the palace made Soerjopranoto and his younger brother, Soewardi Soerjaningrat (Ki Hadjar Dewantara), sensitive to the social problems of the lower classes. He was even willing to give up his Raden Mas title to immerse himself in the lower classes.

Like other aristocrats of his time, Soerjopranoto was projected for a career as a government official. Therefore, he had the opportunity to receive a Western education. He first attended the Europeesche Lagere School (ELS), then continued to the Opleiding School Voor Inlandsche Ambtenaren (OSVIA).

From a young age, he was known as an intelligent and critical young man. His stubborn behavior annoyed the Pakualaman family and the colonial government. Eventually, he was banished to the Middelbare Landbouw School (MLS) in Buitenzorg on the pretext of being schooled.

After completing his studies at the MLS, he obtained two diplomas at once, namely as a landbouwleraar (agricultural science teacher) and landbouwkundige (agricultural expert).

After graduating, Soerjopranoto was appointed by the colonial government as the Head of the Agricultural Service (Landbouw consulent) and the head of the agricultural school in Dieng, Wonosobo.

In Wonosobo, he became more active in the organization by joining Boedi Oetomo (BO). Unfortunately, he considered the organization too conservative. According to him, BO only contained people who lived in desks and rooms and were hesitant to fight for class equality.

After being frustrated with Boedi Oetomo, Soerjopranoto decided to quit as a government employee and switch to an organization he considered more radical, Sarekat Islam (SI). During that time, SI Yogyakarta still needed a solid support base.

Besides being active in SI Yogyakarta, he founded Adhi Dharma Arbeidlseger in 1915. This organization was engaged in the socio-economic field and aimed to improve the welfare of workers. One of the ways it did this was by providing educational opportunities for the native population.

The school founded by Soerjapranoto became a laboratory for his younger brother, Ki Hadjar Dewantara before he founded the Taman Siswa school.

Founded Personeel Fabriek Bond

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, the economic inequality between the natives and the capitalists had become more evident. While private companies were making high profits, the fate of the workers was miserable.

High inflation worsened small salaries, dragging them further into the abyss of misery. Unfortunately, the colonial government abstained from this condition.

The government seemed reluctant to interfere with the capital owners, as they were considered valuable assets for the welfare programs promoted by the colonial government. They only intervened when there was a significant conflict between workers and capital owners.

In the end, the increasingly brutal exploitation of labor stimulated the emergence of labor unions in the period 1918-1919. Soerjopranoto took advantage of this momentum to establish an Arbeidsleger (labor army) called Prawiro Pandojo in Joedo in August 1918 as a branch of Adhi Dharma.

The Arbeidsleger then developed into the Personeel Fabriek Bond (PFB) in November 1918. This organization later became SI’s labor under bow organization.

Soerjapranoto and his group thought it was time for workers to retaliate against the oppression of the owners of capital. Capitalism would be useless if labor as a factor of production stopped working. Strike action was considered the most appropriate breakthrough to teach the owners a lesson.

Coinciding with the establishment of PFB, Soerjapranoto called out in the organization’s first circular that the time had come when the people could have a voice and be involved in lawmaking.

“The age of democracy has come, workers should have equality in the eyes of the law,” he exclaimed. He also criticized the arrogance of capital owners who acted like “God,” firing and exploiting workers at will.

PFB began to show its prowess during the sugar milling season of 1919. At that time, PFB administrators were invited to be orators in the strike of sugar factory workers in Central Java and East Java. This action made the capital owners panic and began considering raising labor salaries.

PFB not only sent its administrators but also established new branches in the places of strikes. In this way, PFB succeeded in organizing strikes and increased its membership to 31,000 people in 1920.

Soerjopranoto’s prestige skyrocketed after being elected as the leader of SI Yogyakarta. Under his leadership, SI Yogyakarta became the most prominent branch, along with SI Semarang, led by Semaoen. Both branches had labor unions. SI Yogyakarta had the PFB, while SI Semarang had the Vereniging van Spoor-en Tramwegpersoneel / Railway and Tram Labor Union (VSTP).

Unfortunately, the golden age of the PFB did not last long. The counter-attack by the capital owners by blocklisting sugar workers who had been involved in strikes deterred most PFB members.

This policy made it difficult for many of them to find jobs after being fired. Gradually, PFB members chose to resign from membership.

Meanwhile, the colonial government, which previously seemed unconcerned, began to pressure company owners to pay more attention to the welfare of workers. Labor wages were gradually raised.

After the policy was issued, PFB’s actions received a different response than before. Finally, this organization also experienced a decline. According to Mcvey in The Rise of Indonesian Communism, in 1922, there were only 400 PFB members left.

Despite the PFB’s decline, Soerjopranoto’s struggle did not stop. He remained active in the Indonesian Islamic Sarekat Party (PSII) and eventually founded the Indonesian Islamic Party (PII) with Soekiman, who was kicked out of PSII.

In addition, he was still active in the press through the newspapers Adhi Dharma, Boeroeh Bergerak (1920), Doenia Baroe (1923), and Suara Bumiputera, which continued to voice labor rights. In the aftermath of his struggle, Soerjopranoto felt the cold of prison bars at least three times.

References

Budiawan. Anak Bangsawan Bertukar Jalan. Yogyakarta: LKiS, 2006.

McVey, Ruth T. The Rise of Indonesian Communism. Singapura: Equinox Publishing, 2006.

Niel, Robert van. Munculnya Elite Modern Indonesia. Jakarta: Pustaka Jaya, 1984.

Shiraisi, Takashi. Zaman Bergerak: Radikalisme Rakyat di Jawa 1912–1926. Jakarta: Pustaka Utama Grafiti, 1997.

Wertheim, W. F. “Conditions on Sugar Estates in Colonial Java: Comparisons with Deli.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 1993, pp. 268–84.