Not long ago, Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI) released surprising information about the destruction of forest land in Indonesia. According to the FWI study, approximately 1.47 hectares of forest land continued to be lost between 2013-2019. This huge number also shows that deforestation is still happening on a large scale. This reality also raises the question of how much Indonesia cares about protecting nature. Conservation efforts in Indonesia are not new but have been going on since colonial times.

The emergence of the Dutch East Indies Conservation Discourse

It is undeniable that the territory of Indonesia used to be one of the lungs of the world, surrounded by many forests. In the 19th century, forests dominated much of the Dutch East Indies continent.

The dense forests of the Dutch East Indies are inseparable from the local people’s awareness of protecting nature. Long before colonial governments set foot in the forests of the Dutch East Indies, locals were already working to prevent deforestation by labeling what is considered sacred and protected forests as haunted.

A region is stated to be haunted for several reasons; however, the most frequent cause is the presence of historic tombs and relics. Because human beings are hardly ever visited, the vegetation in the forest is protected from logging and can be inhabited by endangered animals.

According to a 1908 report by J. S. Ham, the colonial government was responsible for the destruction of the forests of the Dutch East Indies. Forest development in the Dutch East Indies began during the VOC period and peaked in the early 19th century. Logs felled are used to support the construction of various useful infrastructures and facilities for the people of the Netherlands.

To speed up logging, VOC or colonial governments took over local authorities. Large-scale logging for commercial purposes by colonial governments or local populations caused inevitable environmental damage. The situation has sparked concerns among Dutch East Indies scientists about deforestation’s dangers.

In the 1840s, scientists and officials in Batavia began to warn of the dangers of deforestation, which could reduce irrigation water and cause flooding. In addition to scientists, another warning comes from reports from residents of Buitenzorg (Bogor). In his 1847 annual report, he warned governors that deforestation could lead to climate change, reduced rainfall, and, ultimately, the destruction of agriculture.

Concerns about the effects of deforestation are not fictional, as according to the travel reports of German naturalist Franz Wilhelm, who explored Java in the 1830s-1840s, deforestation can be seen in the almost bare mountains of Merbabu, Sumbing, and Sundoro. According to William, deforestation on the mountain disrupted the water supply on the slopes.

Scientists’ concerns were made all the more reasonable because of the unusual weather changes in 1844 at the same time. Unusual weather led to crop failure. Not only did crops fail, but a long dry season followed until 1850.

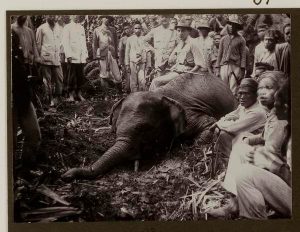

Source: KITLV

Unfortunately, the destruction of nature is also accompanied by large-scale hunting, which may trigger the extinction of some species. According to Robert Cribb in his article titled “Conservation in Colonial Indonesia,” hunting in the Dutch East Indies does at least four things:

- To find food

- To trade

- As a hobby.

- To defend yourself and protect the farm.

The activity has grown substantially since the 17th century, while regulations were not enacted until the 19th century.

This reality further reinforced the awareness of scientists at the time that the dangers of deforestation and hunting were at hand. Therefore, the colonial government inevitably had to find a solution to this problem.

People realized the importance of protecting nature, so the colonial government opened the Cibodas Nature Reserve in 1889 and 1890 through Governments Besluit. This step can be said to be the first conservation step. Ten years later, legal regulations related to animal conservation were issued through Staatsblad No. 497 and 594 of 1909.

Under the rules, nearly all wild mammals and birds are protected from hunting except for dangerous and disturbing animals. Ape species, including orangutans, are excluded from protection. So the regulations do not include a list of protected animals but a list of excluded animals.

Nederlandsch-lndische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming and Regulatory Improvement

In the decade of the 1910s, the conservation movement of the Dutch East Indies began to move. Beginning with the founding of the Nederlandsch-lndische Natuurhistorische Vereeniging (Netherlands Indian Society for Natural History) in 1911, the organization later founded the Nederlandsch-lndische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming (Netherlands Indian Society for the Conservation of Nature) in 1912 to deal with more practical issues. Issues related to conservation.

After the establishment of the Netherlands Indian Society for the Conservation of Nature, it moved quickly to issue a petition in 1913. Through a petition, they expressed their dissatisfaction with the 1909 statute. The 1909 regulation was considered to have many shortcomings because it left too many endangered species, such as orangutans and endangered birds, unprotected.

The petition received a follow-up response three years after the Governor issued the decree in State Document No. 278 of 1916. Through the Act, the Governor can grant the status of a nature reserve to be considered a potential conservation site. In addition, several improvements were made to the 1909 regulations, which were widely criticized.

Regulation improvements to support conservation efforts continue to be carried out as stated in Staatsblad No. 234 of 1924. In the revision of the regulations, all endangered animals throughout the Dutch East Indies are recorded and protected, including orangutans and Javan rhinos.

The 1924 Act also introduced hunting licenses. So not everyone can hunt animals; only those with a license and pay dues can hunt.

While the 1909 and 1924 ordinances prohibited the possession of protected animals, they would have been ineffective without a ban on export trade. To overcome this problem, the colonial government issued new regulations in Staatsblad No. 134 and 266 of 1931, which included a ban on exporting protected animals, dead or alive. The ban includes a ban on exporting fur and animal body parts such as bird feathers and ivory.

As an improvement to the 1916 Act, the Nature, and Wildlife Reserves Act was enacted, Staatsblad No. 17 of 1932. With this provision, the colonial government could create a new category of conservation called a wildlife reserve.

In contrast to nature reserves that offer full protection, human-wildlife reserves are still allowed for small and medium-scale development because it is necessary to maintain the natural conditions of the animals.

The regulation has facilitated the creation of large wildlife reserves such as Baluran in Java (25,000 hectares), Gunung Leuser, South Sumatra, and Way Kambas in Sumatra (both 900,000 hectares).

The laws and regulations of 1931 and 1932 can be said to have been the final framework for the protection regulations of the Dutch East Indies. These two provisions remained in effect until the end of the colonial period and were even adopted by the Indonesian government 30 years after independence.

Bibliography

Boomgaard, Peter. “Forest Management and Exploitation in Colonial Java, 1677-1897.” Forest & Conservation History, vol. 36, no. 1, 1992, pp. 4–14.

Boomgaard, Peter. “Oriental Nature, Its Friends, and Its Enemies: Conservation of Nature in Late-Colonial Indonesia, 1889-1949.” Environment and History, vol. 5, no. 3, 1999, pp. 257–292.

Cribb, Robert. “Conservation In Colonial Indonesia”. Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 9, 2007, pp. 49-61.

Hugenholtz, W. R. ( 1986). “Famine and food supply in Java 1 830- 1914”, in C. A. Bayly and D. H. A. Kolff (eds) Two Colonial Empires: Comparative Essays on the History of India and Indonesia in the Nineteenth Century, Dordrecht and Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 1986.

Indisch Verslag, 1936.

Jepson, Paul, and Robert J. Whittaker. “Histories of Protected Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values and Their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies (Indonesia).” Environment and History, vol. 8, no. 2, 2002, hlm. 129–172.

Kolonial Verslag, 1917.