Some time ago, the Eijkman Institute came to the public’s attention. The news of the agency’s incorporation into the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), and the news that researchers could be fired within it, have had pros and cons in society. Some enthusiastically support the move, but others oppose the policy.

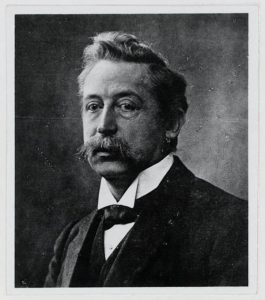

If we look back at the history of this institution, Eijkman is not a new institution. This institution has been established since colonial times. The name Eijkman comes from the name of the Dutch bacteriologist Christiaan Eijkman. Who is Christian Eijkman? Why is his name used as the name of the Indonesian Institute of Molecular Biology? In this article, the author invites readers to gain a deeper understanding of this character.

Christiaan Eijkman’s First Journey in the Dutch East Indies

Christiaan Eijkman was born on August 11, 1858, in a Dutch village called Nijkerk. He is the seventh of ten children.

From the beginning, Eijkman had an interest in studying medicine. Despite financial constraints, he worked hard to realize his dream of studying medicine, enrolling in the Military Medical School of the University of Amsterdam, funded by the Dutch Ministry of War in 1875 (Jansen, 1950: 3).

Christiaan Eijkman joined the army in the Dutch East Indies after completing his medical studies to earn his Ph.D. in physiology.

In 1883, Eijkman sailed to the Dutch East Indies. Meanwhile, the Aceh war was in full swing. Arriving in the Dutch East Indies, Eijkman was immediately stunned by the large number of soldiers paralyzed by beriberi, known in colonial medical circles as polyneuritis endemica perniciosa. Beriberi is a peripheral nerve disorder that causes pain and paralysis that can lead to death if left unchecked.

In his place of duty, he discovered that beriberi had become endemic. Both local and European soldiers contracted the disease. This finding led to the preliminary conclusion that beriberi must have an infectious origin. So he decided to conduct further research to find the source of the bacteria.

Beriberi Research

After two years in the Dutch East Indies, Eijkman was granted permission to return to the Netherlands because his wife was ill. However, his wife died after his return to the Netherlands (Verhoef, 1999:185).

After his wife left, Eijkman devoted his energy to researching the causes of beriberi. He visited Robert Koch in Berlin to learn some basic bacteriological techniques.

There he met Professor Cornelis Pekelharing, a bacteriologist, and Professor Cornelis Winkler, a neuroscientist responsible for beriberi research (Carpenter, 2012: 220).

In 1885, Eijkman returned to the Dutch East Indies as assistant to Pekelharing and Winkler. After a year of research, Pekelharing and Winkler returned to the Netherlands.

Both believe beriberi is an infectious disease caused by micrococcus bacteria that cause nerve cell degeneration. During the study, they isolated Micrococcus bacteria from patients’ blood and claimed that these microorganisms were the causative agent of beriberi. To this end, both advised the colonial government to implement disinfection measures.

However, Pekelharing is not sure if the beriberi problem has been resolved. He, therefore, advised the Governor of the Dutch East Indies to perpetuate the laboratory facilities they had been using and appointed Eijkman to continue research on beriberi (Jansen, 1950:4). The colonial government agreed to the proposal. Still living in the Dutch East Indies, Eijkman was discharged from the military and appointed the first director of the Geneeskundig Laboratory until 1896.

Eijkman himself was not satisfied with the results of the research that his two colleagues had carried out. He also decided to continue research related to beriberi.

In the study, two colleagues used dogs and monkeys as experimental animals, while Eijkman chose chicken because it was more economical to use in large quantities. The decision to use chicken eventually led him to a previously unimaginable discovery.

Eijkman (1929) explained that some chickens in the laboratory suddenly developed polyneuritis, a disease with symptoms similar to beriberi. The chicken was completely paralyzed. The chicken’s condition deteriorated within a few days, so it could no longer eat without help.

At first, he thought bacteria caused the paralysis, so he tried to separate healthy and sick chickens. However, all chickens were still affected by the same symptoms. No more specific microorganisms or parasites were found.

Then suddenly, the disease is eliminated. All infected chickens have recovered, and there are no new cases.

Eijkman began to suspect chicken food. The lab guards reported that from June 17 to November 27, the chickens were fed white rice from the military hospital where the lab is located. At the end of November, the cook was changed, and his successor refused to provide rice for chicken feed, so the chicken feed was replaced with brown rice.

This report corresponds to the time the chickens became sick, which appeared on July 10 and recovered by the end of November (Eijkman, 1929).

Further experiments were conducted to examine whether there was a link between diet and disease. It turned out that the polyneuritis experienced by chickens was associated with a given pattern of eating rice. Chickens fed white rice developed disease after 3-4 weeks, while chickens fed brown rice remained healthy. Eijkman also concluded that there are anti-neuritis compounds in some parts of brown rice seeds that white rice does not.

Adolphe Vorderman, head of the Dutch East Indies Citizens Health Service, read Eijkman’s findings. After reading the work, he immediately interviewed all the civil servants in the district. He found that among the 63 prisons using white rice, 34 had beriberi epidemics, and the rest of the prisons using brown rice had very few cases of beriberi.

With this discovery, the head of health services immediately decided to replace white rice with brown rice in prisons. As a result, beriberi disappeared from the prison population within a short period of time. Eijkman still doesn’t know what’s in brown rice; he calls it an “anti-beriberi factor.”

Back to the Netherlands

Although the light of his research was beginning to appear, Eijkman could not continue his research in the Dutch East Indies. In 1896 he had to return to the Netherlands due to his deteriorating health.

Meanwhile, the High Commissioner for the Dutch East Indies appointed Gerrit Grijns to identify the rice ingredient responsible for beriberi. Grijns successfully complemented his predecessor’s research. He found that the paralyzed chickens were due to a lack of an extra substance he called a “protective agent.” Deficiency of this substance can be cured by feeding green beans.

In 1911, Casimir Funk isolated a substance from rice husks called an amine. Fink also proposed a comprehensive theory that there are substances necessary for life. He called them vitamins. The cause of beriberi was eventually found to be a vitamin deficiency (thiamine) (Piro, 2010:87).

After returning to the Netherlands, Eijkman was appointed Professor of Bacteriology and Hygiene at the University of Utrecht. He subsequently founded the hygiene department in Utrecht. Although he worked on bacterial physiology, he remained interested in studying nutrition and social health.

In 1929, Christiaan Eijkman achieved the pinnacle of his achievements. His extensive work researching the disease beriberi won him the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize also marked the end of his career because, on November 5, 1930, Eijkman died (Pietrzak, 2019: 2894).

Bibliography

Eijkman, Christiaan, and F. Gowland. “Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1929.” HARRISONS PRINCIPLES OF INTERNAL MEDICINE 2 (2001): 2578-2578.

Jansen, B C P. “C. Eijkman, August 11, 1858-November 5, 1930.” The Journal of nutrition vol. 42,1, 1950. Doi:10.1093/jn/42.1.2.

Pietrzak, K. “Christiaan Eijkman (1856–1930).” J Neurol 266, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-9162-7.

Piro, Anna, dkk. “Casimir Funk: his discovery of the vitamins and their deficiency disorders.” Annals of nutrition & metabolism vol. 57,2 (2010): 85-8. doi:10.1159/000319165.

Verhoef, Jan; Harm Snippe; Hans S.L.M. Nottet, “Christiaan Eijkman First bacteriologist at Utrecht University, Nobel laureate for his work on vitamins,” FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, Volume 26, Issue 3-4, December 1999. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01388.x