Who doesn’t know the cinema, one of the most popular places of the century. Almost everyone is always excited when they go to this place. Over time, cinema have become part of people’s way of life. But before it became as popular as it is now, it turns out that Indonesian cinemas have come a long way to be as famous as they are now. In this article, the author would like to invite readers to explore the existence of colonial-era cinema, from its birth to its development.

The Rise of Dutch East Indies Cinema

Films or motion pictures were first shown in Java in October 1896 s(Java-Bode, October 9, 1896), about 10 months after the premiere of the Lumiere Brothers film at the Grand Café in ParisJava-Bode journalists commented on film/motion pictures as an invention of modern knowledge (Java Bode, March 4, 1897).

At first, films were shown only in cinemas and watched by the elite. In 1897, the film was shown in a place where a large audience could be seen.

Movie screenings have grown to an ever-increasing audience after screenings in tents in villages and squares in Chinatown. By 1905, movies at the Night Market or Gambier Market had become public entertainment.

Movies quickly became popular entertainment in urban areas. On October 12, 1905, the daily reporter Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië clearly described the turbulent atmosphere surrounding the cinema.

“Life seemed to revolve around cinema. Young girls started flirting in the afternoon. Locals were stealing, caught saying they didn’t have money for movie tickets. A father complained that his daughter went missing after going to the movies. Staff asked for advance notice Payments, not because the family died, but because they wanted to take the family to the movies. Even the local laundry lent his friends his white pants and shirts so he could go to the movies.”

From the very beginning, movies have acted like a magnet, able to arouse the interest of different groups. Whether they are employees, nobles, businessmen, or even the lower middle class.

But don’t think the cinema that came out at the turn of the century were as great as they are today. The resulting cinema was originally set up in a semi-permanent tent with bamboo poles and cushions.

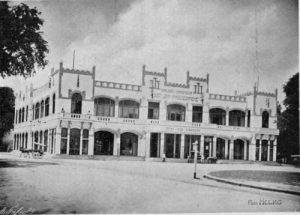

Only a few years later, the brick-walled cinema was built. The East Java Bioscope in Surabaya was inaugurated in 1913 as the first permanently built cinema.

Colonial Tickets and Movies

At the start of his performance, moviegoers had to shell out. The ticket price for watching a movie is still very expensive, about 1-2 guilde. However, as audience interest has grown, ticket prices are slowly being lowered to cover more residents.

At the beginning of the 20th century, movie tickets became diverse, divided into European, foreign oriental and indigenous races.

The cheapest tickets are for Indigenous audiences, starting at f0.25 and dropping further down to 0.10ft and sometimes as low as f0.002.

The most expensive tickets were sold to Europeans, but there is no accurate record of ticket prices. However, colonial film regulations did not allow European audiences to sit in native seats.

However, these provisions are often ignored because not all inhabitants belong to the elite group, so they often do not hesitate to sit side by side with Far Eastern and indigenous groups.

The difference in fares also marks a difference in the seating position when viewing. Of course, the European seats are the most comfortable part of the movie theater. Cinema owners do everything they can to make European audiences comfortable.

The Nederlandsch-Indische Biograph Compagnie provided a gramophone for the performance. Meanwhile, Siren Bioscope, a Chinese cinema in Surabaya, has adorned the walls of the cinema with wallpaper and ventilation and lighting for European audience seats. Another cinema in Surabaya has a luxurious balcony on the top floor, offering unobstructed views to European audiences.

For Indigenous audiences, the opposite is true. In each cinema, the position of the indigenous audience is different, some are at the top, directly in front of the screen or commonly known as the goat seat, or behind the screen. The final layout resembles the Wayang behind the screen where the viewer is watching the shadow effect. The viewing position behind the screen is the cheapest in the seating class.

At the time, imported films such as Georges Méliès’ “The Voyage of the Moon” dominated the release. Other films such as Bluebeard, Alibaba and 40 Thieves, Nyai Dasima were also screened.

Movies are not to be watched silently. In addition to the clicks of machines and other audience noises, the performance is accompanied by a gramophone or automatic musical instrument. Additionally, a narrator is used, who accompanies the film throughout the film.

As easy as it might seem to wear today’s glasses, showing a movie in a movie theater always leaves audiences in awe. According to the reporter Soerabaiasch-Handelsblad on November 25, 1904, every time the movie opens, the audience will “waah”, and while watching the movie, they also express their feelings, such as “Ya Allah, Tobat”, when they said they saw a tense scene.

That’s what’s so exciting about colonial-era cinema. Not only is the cinema a symbol of modern inventions, it is a place that still attracts attention to this day.

Bibliography

Java-Bode, 9, Oktober1896.

Java Bode, 4 Maret 1897.

Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 12 October 1905

Nordholt, Henk Schulte. “Modernity and middle classes in the Netherlands Indies: Cultivating cultural citizenship” in Susie Protschky (ed.), Photography, modernity and the governed in late-colonial Indonesia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015.

Ruppin, Dafna. “The Emergence of a Modern Audience for Cinema in Colonial Java.” Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde, vol. 173, no. 4, 2017, pp. 475–502.

Soerabaiasch-Handelsblad 25 November 1904.

Stoler, Ann L. “Making Empire Respectable: The Politics of Race and Sexual Morality in 20th-Century Colonial Cultures.” American Ethnologist, vol. 16, no. 4, 1989, pp. 634–660.

Taylor, Jean Gelman. “Ethical policies in moving pictures: The films of J.C. Lamster” in Protschky, Susie, editor. Photography, Modernity and the Governed in Late-Colonial Indonesia. Amsterdam University Press, 2015.